Vanuatu Biorock Coral Reef Restoration Workshop

Havannah Harbour, Efate, June 9-18 2016

Tom Goreau

Robert Lee

Leah Nimoho

Iman Garae

SUMMARY

More than 100 people attended the First Vanuatu Biorock Coral Reef Restoration Workshop, held June 13-14, and installed the first Vanuatu Biorock projects at three sites in Havannah Harbour, northwest Efate.

Participants included many fishermen from local villages, especialy Tanoliu (Port Havannah), from other communities on Efate, including Tasi Vanua, the North Efate reef monitoring group, community-based environmental protection groups from Nguna and Pele Islands. The Tasi Vanua group members from Nguna and Pele have been trying for several years to restore the coral reefs on those islands using conventional methods, but have been unsuccessful and have been actively seeking a more successful approach. Students from the University of the South Pacific, Ulei Junior Secondary School, and Tanoliu Primary School, members of the Vanuatu Environment Science Society, and interested members of the local community were all in attendance. They received hands-on training in design, construction, installation, monitoring, maintenance, and repair of effective coral reef fisheries habitat restoration projects.

The workshop was taught by Dr. Tom Goreau, President of the Global Coral Reef Alliance, who has done such projects for nearly 30 years. Dr. Goreau trained the Yayasan Karang Lestari team in Indonesia who won the United Nations Equator Award for Community Based Development and the special UNDP Award for Oceans and Coastal Management at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 2012.

The workshop was was organized by Robert Lee, a US Peace Corps Volunteer, Leah Nimoho of the United Nations Development Programme Office in Port Vila, Vanuatu, and Iman Garae, Headmaster of the Tanoliu Primary School.

Following a failed coral garden project, Robert Lee, a teacher in the elementary school at Tanoliu (site of the World War II American military base at Port Havannah), researched coral reef restoration, discovered the Biorock method, and found enormous interest in Vanuatu about learning more effective methods.

Leah Nimoho of the Vanuatu UNDP Small Grants Program and Robert Lee worked for two years to seek funding from UNDP to the Vanuatu Fisheries Department to hold a Biorock Training Workshop. Mr. Iman Garae, Headmaster of the Tanoliu Primary School, brilliantly managed local logistic arrangements, including transportation, food, and community participation.

Special thanks also go to Mr. Graham Nimoho and Mr. William Naviti of the Vanuatu Fisheries Department.

Nothing would have happened without all their hard work, persistence, and strong support from Vanuatu environmental organizations and communities. We are grateful to all who participated.

All photos by Robert Lee or Iman Garae

PAST AND PRESENT CONDITION OF VANAUTU CORAL REEFS

Vanuatu coral reefs are among the best in the world in terms of coral live cover, biodiversity, and large size, comparable to the best Indonesian and Palau reefs before the 1998 bleaching. Yet little work has been done on the condition of the coral reefs, and through a serious scientific/political error they were not included in the Coral Triangle Initiative, which includes Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands.

In the past the islands were much more densely populated than they are today, and there must have been impacts of land-clearing for agriculture on the coral reefs of these high, wet islands. Almost the entire population died from genocide caused by European diseases, and the survivors were largely wiped out by the European slave trade “blackbirders” who would round up villages at gunpoint and force them into “indentured” labor in Australian sugar cane fields or Pacific coconut plantations. The islands were occupied by French and British colonists, who forced the population to cut down much of the coastal forest for coconut plantations and the people to work at subsistence wages preparing copra. The impacts of this erosion are clearly seen in muddy silted coastal lagoons with dead coral reefs on the south coast.

In 1943 the islands of Efate and Espiritu Santo were suddenly occupied by the US military, who brought in some 150,000 men to build large military bases for bombing, and then invading, the Solomon Islands in order to drive out Japanese troops. In less than one year the islands were transformed and the troops moved on, dumping vast amounts of war material into the sea. Havannah Harbour was the major base on Efate, and most of the fringing reef on the south coast of the harbour was dredged or destroyed for landing crafts and boat traffic. What coral came back was dominated by Porites head corals in shallow water, and Porites branching corals in deeper water. These low biodiversity reefs are typical of those that have been severely stressed by high sedimentation and high temperatures until almost all the other corals have died, leaving Porites as the last survivor. In contrast to these reefs on the south side of Havannah Harbour, those on the north side, as well as those on the open ocean side north of Moso Island, were dominated by Acropora. Porites head and branching corals, which can have very high live coral cover, do not provide the ecological services of biodiversity, fish habitat, and shore protection that the Acropora corals do, producing functionally impaired habitats.

Since most of the steel trash has rusted away, the beaches are distinguished by extraordinary amounts of glass, apparently mostly from millions of Coke bottles drunk by American troops, tossed into the sea, and used for gun target practice. The islands then returned to a coconut plantation economy, which since Independence have been largely replaced by cattle ranches and small farms. There is no industry, and the vast majority of the people are farmers, producing lush tropical crops from the rich soil. The growth of the population over the last 50 years has been very rapid, currently growing by 2.2% per year, causing increased pressure to clear forest land for cultivation, in particular kava, which Vanuatu people are especially fond of.

Following earlier damages by dredging and sedimentation, the growth of the population, and the lack of sewage treatment facilities, have caused weedy algae overgrowth (eutrophication) of reefs near major urban areas, such as Port Vila. In recent years Crown of Thorns outbreaks have killed a lot of coral. New coral diseases, especially White Plague, are starting to have an effect. But in the last year the major cause of coral mortality has become bleaching. Coral bleaching in Vanuatu was predicted in April based on the Satellite Sea Surface Temperature HotSpot data by Tom Goreau. June dives confirmed that Vanuatu was recovering from a major bleaching event. The excess temperature was only around 1 degree C for a month, enough to trigger mass bleaching but not severe coral mortality. Recent coral death at the reefs dived on ranged from low to moderate, with perhaps 20-30% mortality at the most affected sites, much of it partial mortality (usually the tops of the colonies), with lower mortality at sites with high turbidity due to protection from high light stress during high temperature bleaching. At these sites bleaching seemed to be the major cause of coral mortality but most of the corals were gradually regaining their normal colors (see photo below). Since bleaching is the result of global warming, such events will be more frequent in the future.

Vanuatu coastal villagers are all excellent swimmers, are exceptionally aware of the recent decline in their coral reefs, and are unusually worried about these trends. As a result many villages have started their own coral nursery projects, copying the standard methods used around the world, with precisely the same results: almost all the corals died. The international funding agencies that promote such projects never show long-term results for a very good reason! But they never report their failures, because that would prevent getting more money to repeat them! But unlike most, Vanuatu people quickly realized that they needed more advanced methods of reef restoration that increase coral settlement, growth, survival, and resistance to environmental stresses like high temperature, sediments, and nutrients, which only the Biorock method does.

A Hawksbill turtle swims over coral reefs on the north shore of Havannah Harbour. Almost all the coral colonies in this photo are slowly recovering their color from bleaching. Photo June 12 2016 by Robert Lee.

WORKSHOP RESULTS

A two day-long hands-on training workshop was held at the Havannah Beach and Boat Club, thanks to the permission of the owner, Jonathan Delaney.

Videos were shown of the results of Biorock coral reef restoration projects in Bali, which were awarded the United Nations Equator Award for Community-Based Development, and the special UNDP Award for Oceans and Coastal Management, at the 2012 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro.

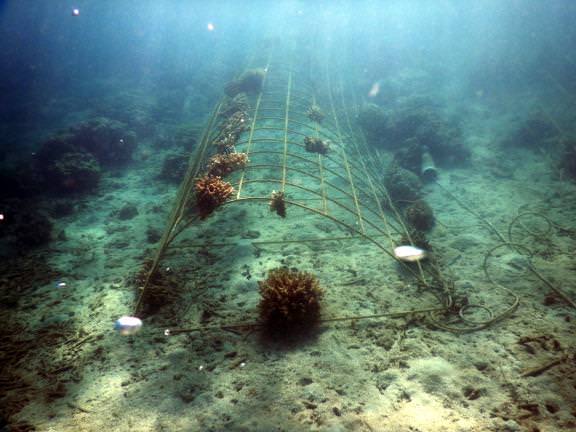

A lecture discussed the principles of project design for different purposes, focusing on coral reef fish habitat restoration. The group then built the first two structures, tunnels made from welded steel mat and rebars. Then the group built a large dome.

Hands-on training.

On the second day the group wired and installed the two tunnels in water about 2 meters deep at low tide on the inside edge of the reef in front of the Havannah Beach and Boat Club, installed the electrode and power source, and turned it on. The event was documented by drone filming done by Marke Lowen of the Vanuatu Museum Film Archive, to be broadcast by the Vanuatu Museum free cable TV channel. Then the group carried the dome to the Havannah Eco Lodge (Gideon’s Landing) and installed it in water about 5 meters deep, wired up the structure and electrode, and laid the cable. The power supply was not available until the following morning, when it was turned on.

The group from Tanoliu, eager to practice and improve their skills, then immediately built another dome, about 2 m high and 4 m wide, which was installed and wired up the following day. Like all the other projects, they worked immediately when connected.

Biorock dome at the shore of Tanoliu being prepared for installation in the water.

Celebrating the installation of the dome at Tanoliu, on the bottom near the float.

The Tanoliu group spent a half day being instructed in coral transplantation, focusing first on adding corals to the tunnel structures from local naturally broken coral fragments found on the reef.

Several post workshop follow-through training sessions on coral transplantation were given at Tanoliu with the local team, including Robert Lee, who trained members of Tasi Vanua, a North Efate coral reef monitoring organization, in the methods, and built and installed more structures.

Lectures were also given at the University of the South Pacific on the Future of Coral Reefs, and at the Vanuatu Environment Science Society on the Past, Present, and Future of Vanuatu Coral Reefs. A local newspaper, The Independent, ran a special two page article on the workshop.

Restoring their villages coral reefs: A day these Tanoliu students will never forget! They’ll come back again and again to see the corals and fish!

NEXT STEPS

The Training Workshop was Phase I of the project. Once all the expense accounting has been submitted, funding for Phase II will be released by UNDP.

Phase II will be scheduled as soon as possible after the funds are approved to continue the momentum and to build on the enormous enthusiasm which the first workshop generated. The major goals include:

1) Documenting the results of all the pilot projects installed at the first three sites, and assessing them to decide how they could be best improved and expanded.

2) Establishing a local cooperative for sustainable mariculture projects at Tanoliu focusing on culture of giant clams and habitat for groupers.

3) Expanding the projects to new sites around Efate and other islands. Already at least half a dozen groups want similar projects.

4) Making Vanuatu the Pacific leader in coral reef restoration, sustainable marine resource management, and adaptation to climate change.

5) Expanding the UNDP Small Grants Programme to support more community-based marine habitat restoration and management projects in Vanuatu, and in other coral reef subsistence fishing communities around the world.