Thomas J. Goreau

Wolf Hilbertz

A. Azeez A. Hakeem

May 1, 2004

We all treasure our blissful interludes on the shoreline, accompanied by the breeze, and sound of waves lapping at the shore, especially during the magic moments of sunset and sunrise. However, it is all too easy to think of the shoreline as an immutable haven of peace.

In fact, it is a highly dynamic place, constantly dancing to the vagaries of the winds, waves, tides, and now, to global climate change. Consequently, almost all of the world’s beaches are vanishing, not just being inundated but actually retreating, washing away into the sea. The major exceptions are those near rivers engorged with sand and mud from the erosion of deforested watersheds, or where sand carried by longshore currents pile up behind jetties and other man-made obstructions, starving the beaches down-current of sand.

Tropical white sand beaches are an especially tranquil place. What makes tropical beaches so calm and well protected are the coral reefs that grow in front of them, producing the white sand, each grain of which is the skeletal remnant of a living reef organism, while protecting it from waves and currents.

When the corals die, the beach suffers a double blow. First, the supply of new sand decreases as the animals and plants producing them vanish. Secondly, as the dead coral reef framework crumbles under the relentless attack of waves and boring organisms (as diverse as bacteria, algae, fungi, clams, worms, and fishes), the erosive wave forces on the shoreline dramatically increase. When the corals die, so does the beach, eventually.

All around the world the corals are dying. There are many causes, but the major one is global warming, caused by the fossil fuel addiction of people often on the other side of the world. Global warming has an equally evil twin, global sea level rise, caused by the melting of glaciers and ice caps, and the volumetric expansion of warmer oceans. The result of this double onslaught is that almost all the white coral sand beaches of the world are vanishing with ever increasing speed before our eyes.

The most serious effects are in the world’s lowest lying islands, where the winds may have piled beach sand no more than a few meters high. Whole nations, the Maldives in the Indian Ocean, and Tuvalu, Kiribati, Tokelau, and the Marshall Islands in the Pacific, along with thousands of other low islands around the world, could vanish entirely in the coming generation—as could most of Bangladesh.

Shore maintenance and protection is probably the largest single cost of global warming, but no international of government agency takes responsibility for preventing it. Instead, they wait for seawalls, roads, buildings, and airport runways to collapse into the sea after storms, and then may grant one-time emergency aid to desperate governments. The World Bank, the Global Environmental Facility, and the United Nations Development Programme all have told us that coastal protection was not their problem.

Recently we tried to use the web to find out how much the world currently spends on coastal protection, knowing that the current rate of sea level rise, about 2-3 millimeters per year, will increase dramatically in future decades as ice melting accelerates, perhaps with catastrophic surges. All of our searches on “shore protection” yielded nothing but compendia of banks in the Cayman Islands and other places, listed under “offshore asset protection”! The world is asleep at the wheel when it comes to protecting our beaches for our children’s children.

It would be hard to find a more vulnerable place than the Maldives, the lowest lying country in the world, meriting its own entry in the Guinness Book of Records. Every one of the Maldives’ 1200 islands, 200 of them inhabited, are suffering from erosion. On all but one (explained below), one can see coconut and Pandanus trees lying dead in the sea after the sand holding their roots washed away.

The Maldives have been a center of civilization for over 5,000 years. Maldivian shells were traded to the ancient Indus Valley cities like Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, whose characteristic manufactured beads are found in the Maldives. Unique among coral reef islanders, Maldivians do not eat reef fish. They specialize in hand line fishing of tuna in deep blue offshore waters, and they have maintained these resources sustainably for millennia, until foreign fleets with drift nets and long lines with multiple hooks began decimating their tuna stocks.

Able to produce nothing but tuna and coconuts, the Maldivians escaped direct colonial rule, becoming a remote British protectorate “managed” from India under home rule. The Maldivians were poor subsistence fishermen until recent decades, when an airstrip on islands joined by dredging brought in floods of European tourists to enjoy the perfect white sand beaches and the best coral reefs in the Indian Ocean. Now their unexpected prosperity is suddenly imperiled by global climate change.

Maldivian homes were traditionally built from corals, cemented by quicklime made by burning corals in kilns fired by coconut wood. When there was an abundance of corals and few people, the impacts on the reef were minor. Now, almost all the reefs around Male, the capital island, which has 80,000 people on two square kilometers, have been mined bare of corals for construction. In 1987 and 1991 the island flooded, because there were no reefs to protect it from storm waves. The groundwater was contaminated with salt.

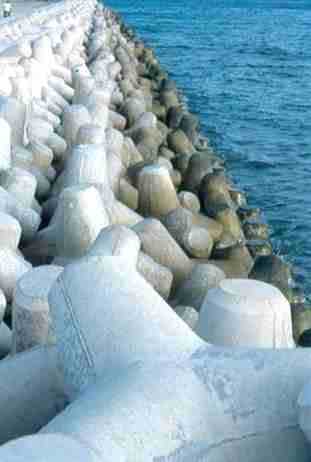

Following this disaster, the Japanese Government gave the Maldives aid to build sea defenses around Male to prevent flooding. Now there is hardly any natural shoreline left, and a jagged wall of giant concrete tetrapods, cast and shipped from Japan, surrounds the island. There is hardly a sadder shoreline than these kilometers of lifeless concrete, a sterile linear barrage. Now, there are no more shoreline coconuts or pandanus trees to fall into the sea. The concrete wall cost around US$ 13 Million per kilometer, or &13,000 for each meter! This foreign aid was absorbed by the capital island, and did not reach the other 199 inhabited islands or tourist resort islands. So these have simply mined the nearest reefs and piled the dead corals into walls around the islands. These walls are eventually destroyed by storms, and then need to be rebuilt. The wealthiest resorts have used steel wire cages, or gabions to enclose the dead coral. These rust and fall apart, with the same result, but a few years later

In 1998, the hottest year in history so far, between 95% and 99% of the corals in the Maldives died from heat stroke. There has been some slight recovery since, but it will take decades to regain what was lost, and the Global Coral Reef Alliance’s long-term satellite records of sea surface temperature increase in the Maldives suggest that such events will soon become annual. So now there are few corals and many people, and the old strategies can no longer work, even if the sea level was not rising.

Starting in 1996, we began growing coral reefs in the Maldives, using the new Biorock technology. This uses very low and safe direct electrical currents, often provided by solar panels or other sustainable energy sources, to grow sold limestone structures in the sea and greatly speed up coral growth and survival. On the Biorock reefs, the survival of corals in 1998 was from 16 to 50 TIMES higher than on the surrounding reefs.

The corals we were growing were simply healthier, and had more energy to resist environmental stress. As a result our reefs are the only ones left in the Maldives that are up to 100% covered by living corals, and they have maintained large populations of fishes that have virtually vanished from nearby reefs because they will only live in live corals, and reject the dead variety. The high densities of live rapidly growing corals and dense swarms of brightly coloured fish have made them an immense attraction to tourists.

However, there is a much more serious purpose to these projects than for ecotourism. By keeping corals alive under lethal conditions and restoring coral reefs where they cannot recover naturally, we aim to restore the reef and its fisheries, to keep ecosystems from going extinct from global warming, and to protect the shoreline from vanishing under the waves.

One of our major goals is to develop a sustainable technology that can keep the Maldives and other such islands from disappearing. For this reason we started growing a reef in front of a severely eroded beach on the tourist resort island of Ihuru, in North Male Atoll, only 15 minutes from the capital, Male by speedboat. The project is 45 meters long (140 feet), about 4-8 meters wide, and 1.5 meters high. It was constructed of welded construction steel rods at a cost of a few percent of a concrete or rock wall. This structure was called the Necklace, because it was intended to be the first stage in restoring the ring reef around the entire island and protecting its lovely beaches without concrete, dead coral walls, or plastic mesh bags pumped full of sand, which invariably disintegrate, rip, and leave plastic debris littering the sand..

The results have been astonishing. When it was built the structure lay amid the best snorkeling reef in any tourist island in the Maldives, but in 1998, almost all the surrounding reef corals died when water temperatures reached up to 34 degrees C. In contrast, most corals on the Necklace survived. The Necklace reef has become a haven for fish, like Giant Moray eels, sweetlips, triggerfish, and others now rarely seen on the dead reef. Fish line up patiently to be groomed by cleaner fish and shrimps, making it an ideal place to see many kinds of fishes behaving without aggression to each other.

The effect on the beach has been even more incredible. As the limestone rock reef and the corals on it grow more massive, the waves that once surged right through it to batter the beach now slow down as they pass through, as the friction of the growing surface constantly increases. As a result sand once held in suspension is falling out, burying the structure from the bottom up.

In the last two years, the once-eroding beach has grown by 15 meters, and the sand is now forming a sandbar pointing right to the structure. Unfortunately, the hotel whose beach is being protected regards the reef more as a tourist attraction than as shore protection, and so has not extended it around the island as intended. Instead, they spend a fortune pumping sand to maintain their beaches from vanishing. Instead of applying this technology, developed in the Maldives to save the entire country from drowning, to every island, the example is dismissed as a mere gimmick to trap tourists with bright corals and fish. We can only hope that it is applied on the scale needed before it is too late. Then future generations of Maldvians and tourists will continue to enjoy their idyllic moments of peace on the shoreline while this unique country grows its way out of the very real threats of global warming and sea level rise.

Image gallery:

For the projects described in this article, Tom Goreau, President of the Global Coral Reef Alliance, a non-profit organization for protection and management of coral reefs, and Wolf Hilbertz, President of Sun & Sea, a non profit organization for developing sustainable construction technology using materials grown from sea water, received the Theodore M. Sperry Award, the top award for “Innovators and pioneers in restoration”, from the Society for Ecological Restoration, and Azeez Hakeem received the Maldives Environment Prize. These projects, and similar ones in over a dozen countries around the world that have won the SKAL Award for best Underwater Tourism Project in the World, and the KONAS Award for best Community-Based Coastal Zone Management Project in Indonesia, have all been done without any support from governments or international funding agencies.

For more information on this project, see: Maldives Nurses its Coral Reefs Back to Life Reuters, Alan Wheatley, May 2, 2004